Contextualization is a big word to say that the Gospel is presented in the local language and cultural forms. It can also be understood as making the Gospel message and the church relevant to society or to a culture. In this conception, forms of worship, music, and church programs are changed to make them fit contemporary society or a different culture. Eventually, this may extend to modifying what the church teaches where older teachings are considered out of touch with, or even reprehensible to, society at large. The goal of this kind of contextualization is to draw in more people – to be more relevant.

Some assume, wrongly, that this is what everyone means by contextualization. But there is another kind of contextualization. The church planter, speaker and researcher, Ed Stetzer, says it well:

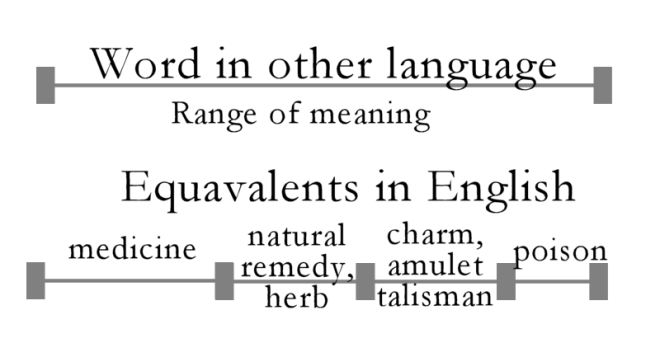

I have said it many times, but it always seems to bear repeating– contextualization is not watering down the message. In fact, it is exactly the opposite. To contextualize the gospel means removing cultural and linguistic impediments to the gospel presentation so that only the offense of the cross remains. It is not removing the offensive parts of the gospel; it is using the appropriate means in each culture to clarify exactly who Jesus was, what He did, why He did it, and the implications that flow from it.

I subscribe to this kind of contextualization.

A while back, I heard a preacher criticize Campus Crusade for changing their name including dropping the word “crusade”. This preacher saw that as an act driven by fear of offending a certain group. But the word “crusade” does not appear in the Bible. For me its primary meaning is a large evangelistic meeting. But for much of the world it brings a message of forcing people to change their faith through military action – something quite against Jesus’ message.

I have seen other cases where fear of watering down the message was applied in such a way that it distorted the real message. I know that the message of Jesus can be controversial. That does not bother me. What bothers me is presenting something that is controversial and alienates people, but which is NOT the message of Jesus. It seems to me that the word “crusade” can do exactly that.

I am sad to say that some people seem more concerned that they make a clear stand against certain people or groups than that they accurately represent Jesus. Standing against a certain group makes a message look strong and uncompromising, but it almost inevitably distorts it all the same. Our approach to translating the Bible focuses on accuracy – “removing cultural and linguistic impediments” so that only the original meaning remains. Pleasing any particular group is not our concern, nor is standing against any group.

I am proud of the good news! It is God’s powerful way of saving all people who have faith (Romans 1:16)

I try to find common ground with everyone, doing everything I can to save some (I Cor 9:22)