It is fascinating to see how translations of the Bible are recieved. Books are written about translations of the Bible into English extolling their virtues or exposing their weaknesses. Some give new translations kudos and other castigation. This kind of reception for new translations is not at all new. In fact, the history of what was said about new translations reveals a pattern.

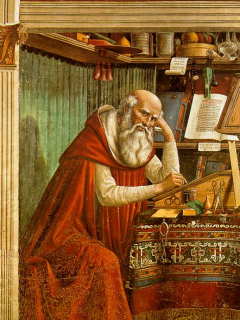

In 382 AD, Euseius Hieronymus, later known as Saint Jerome, was asked to produce a new translation of the Bible in Latin to replace the Old Latin Version which some considered divinely inspired – once for all delivered for all believers. Jerome was highly qualified for the task. But, when his translation appeared it was not widely accepted. It took some time, but his translation was finally recognized for what it was – a work of great accuracy, beauty and skill.

But that was only after Jerome’s death. Then people started saying about his translation exactly the opposite of what its critics said when it first appeared. In fact, they said that Jerome’s translation had all the qualities — accuracy, eloquence, clarity — an earlier generation said only belonged to the Old Latin Version.

In the late 1800s, the Swiss theologian Louis Segond did a translation into French from the original languages because the existing French translations were all over 100 years old. When it first appeared in 1880, it encountered a firestorm of criticism from French protestants, especially from more conservative churches. Nevertheless, it eventually it became the standard translation, occupying a place similar to the King James in English. Revisions in 1978 and 2007 are still the most popular Bibles among French protestants, while the revision done in 1910 is still widely used in French-speaking Africa. When newer translations in French started to appear in the late 20th century, many protestants defended Segond’s translation, saying that it was more accurate whereas their grandfathers and great-grandfathers, often members or leaders of the same churches, had criticized its accuracy.

When the King James Version first appeared in 1611 many Puritans continued to use the Geneva Bible, even printing it after that was outlawed. As late as 1800, almost 200 years after the King James was first published, some Puritan families were still using the Geneva Bible. In fact, it was the Geneva Bible that the pilgrims brought to the New World, not the King James. After the first publishing of the King James Version a renowned Hebrew scholar named Hugh Broughton became its strongest critic. Upon receiving a courtesy copy of the first printing, we wrote a blistering critique. But the opposition died away and the King James Version became synonymous with the Bible for English speakers.

So, it is entirely predictable that when a new translation appears, there will be claims that a well-established older translation is better because it is more accurate, more beautiful and/or more holy.

The same thing is happening today in Ghana. The first translations of the Bible appeared into the Ga, Ewe (pronounced eh-vay), and Twi languages in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The Bible Society did revisions in the late 20th century, but some people still come to their sales points asking for the original versions because they believe that they are more accurate, beautiful or holy.

The same will happen, alas, to the translations in which we have been involved when they are revised.

If you liked this, you might also like Why New Translations.